“He behaved like a brute… the most hardened creature I have ever met.”

FLORENCE NIGHTINGALE TO HER SISTER FRANCES PARTHENOPE VERNEY, 1855

They met on a blazing October day at Scutari, now Üsküdar in Istanbul, at the height of the Crimean War: the ‘lady with the lamp’, grave, chaste, demure, and hailed as a pioneer of nursing and a heroine in Victorian England, and the short, slight, irascible, aging lieutenant-colonel who had been appointed deputy inspector-general of hospitals for the British army in May of 1851, Dr. James Miranda Barry.

The antagonism was mutual. Florence has been described as intense and driven, and accused of racism for her icy attitude toward Mary Seacole, the mixed-race Jamaican ‘doctress’ who had applied to join Nightingale’s nurses and served, when rebuffed, as a sutler privately providing care, nourishment and accommodation to wounded soldiers on the supply road from Balaclava. But this was a clash of titans, neither of whom ever yielded to other authority, civil or military. Barry, so obsessed with hygiene that he would mutter, “Dirty beasts! Dirty beasts! Go and clean yourselves!” when inspecting the troops, was not impressed by Nightingale’s standards at Scutari and lectured her in the presence of her subordinates. Nightingale’s response was glacial, perhaps because she had been publicly castigated, and no one who had ever been on the receiving end of one of Barry’s tirades ever forgot it; or perhaps it was a visceral reaction to what she saw or sensed, a sexual challenge that offended the devoutly Christian Nightingale, who had no great affection for her own sex and preferred the company of powerful men.

This uniformed martinet in the scarlet coat with the heavy epaulettes and insignia of rank, and the sword and the spurs and the tightly trousered, booted legs, lecturing her from the saddle, was a woman.

She had been born Margaret Anne Bulkley in Cork, Ireland, about 1789, the daughter of Jeremiah Bulkley, grocer and inspector at the Weigh House, a position of responsibility not often granted to a Roman Catholic, and his wife Mary Anne, née Barry, sister of the renowned Irish painter James Barry, a Fellow of the Royal Academy of Arts in London.

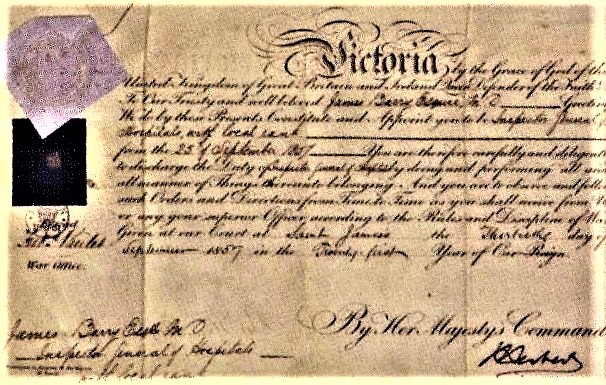

Dr. James Miranda Barry, miniature on ivory

She was a pretty, spirited child with red-gold hair and blue-green eyes, and the characteristic Barry hooked nose and small, sweet mouth. Fastidious in everything from the choice of her clothing to the penning of letters on Mary Anne’s behalf to James Barry, asking for financial assistance as the family fortunes declined and Jeremiah was dismissed from the Weigh House in a British backlash against Irish Catholics after the French invasion of 1798, Margaret Anne Bulkley was indubitably female, as was confirmed after her death when those preparing her body for the undertakers found her to be “a most complete and perfect woman.”

There were also indications on that body that ‘James Barry’ had borne a child, and it is probable that Margaret was raped at about the age of thirteen, the most likely suspect being her dissolute uncle Redmond Barry, a sometime sailor who washed ashore occasionally, in and out of debt, debtors’ prisons, and the Royal Navy. What is known is that Mary Anne Bulkley and her daughter Margaret disappeared into the country for some time and returned with a baby girl, who was named Juliana for Mary Anne’s mother and who was, allegedly, Margaret’s sister. And while this child was never acknowledged, nor, eventually, was any other vestige of her former life, ‘James Barry’ remained notably fond of, and affectionate toward, children and small animals, and was instinctively trusted by them, to the extent that in the Cape Colony where Barry subsequently spent many years, local children would fearlessly call him the kapok nooientjie, the “little kapok maiden”, not only for his delicate physical appearance but for the stuffing with which he padded his trousers and coats to simulate anatomical correctness. Barry would later use custom-made prosthetics, presumably supplied by London theatrical costumiers, to achieve the same effect.

The anticipated financial aid never materialized from the painter James Barry, and mother and daughter made yet another pilgrimage from Cork to London to claim a share of his estate when Barry died intestate in February of 1806. Little money was forthcoming, but Barry’s friends and patrons, among them doctors, lawyers, the Earl of Buchan and the Venezuelan patriot and diplomat Sebastían Francisco de Miranda y Rodríguez de Espinosa, took a paternal interest in Margaret, mentored her, encouraged her passion for learning, and almost certainly suggested the risky charade that would determine the course of her life. It had been done before by Margaret, Countess of Mount Cashell, near Cork, a pupil of the radical feminist Mary Wollstonecraft who had left her titled husband, taken a lover more kindly disposed toward the emancipation of women, and as a six-foot, muscular female in male clothing had attended medical lectures in the university town of Jena in Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach. A Cork girl herself, and one who had once written to her brother, “Were I not a girl, I would be a soldier,” Margaret Bulkley must have been intrigued by the story.

And Miranda had a vision of a republican Venezuela where men and women would be equal. Margaret could accompany him there and practise medicine openly.

On Thursday, November 30th, 1809, Margaret Anne Bulkley disappeared, and a young ‘nephew’ and namesake of the painter James Barry took ship for Edinburgh, accompanied by his ‘aunt’, Mary Anne. He applied to and was accepted by the university, and joined hundreds of other male medical students. Three years later, after countless lectures and dissections and courses in anatomy, pathology, military surgery, medical botany and, particularly, midwifery, and oral and written examinations in Latin, ‘James Barry’ was awarded his degree.

James Miranda Barry as a medical student, unauthenticated portrait

For Margaret Anne Bulkley, now a qualified physician, the dream of reassuming her female identity and joining General Miranda in Venezuela was abruptly and hideously shattered. As described by Michael du Preez and Jeremy Dronfield in their compassionate and evocative biography, Dr. James Barry, A Woman Ahead of Her Time (Oneworld Publications, 2016) Miranda had “returned with [Simon] Bolívar to Caracas, where he received a mixed reception… his idealism was at odds with Bolívar’s authoritarianism. Following a year of violent turmoil and political intrigue, he was betrayed by Bolívar. Accused of treason, Miranda was handed over to the Spanish royalists and taken back to Spain, where he was thrown into a dungeon in the Arsenal de la Carraca in Cadíz. He never saw freedom again.

“There would be no Venezuelan dawn for Margaret Bulkley.”

For Dr. James Miranda Barry there were London dawns at St. Thomas’s Hospital, following the great surgeons on their rounds, observing the distressing lack of hygiene on the wards, and learning, always learning. But money remained a problem, and in June of 1813 Barry presented herself to the army medical board and applied to be accepted as a surgeon, giving her age as eighteen (she was about twenty-four). Considered a prodigy but certainly not a woman, she passed the examinations required by the Royal College of Surgeons and was commissioned as assistant staff surgeon in the British army on December 7th, 1815. An attractive, androgynous and unusually youthful figure in plain single-breasted scarlet coatee without epaulettes, as befitted an assistant surgeon, she sailed for the Cape Colony in 1816; and, having obsessively guarded her privacy throughout the long sea passage from England, set her booted feet with their two-inch heels on the soil of Africa in October.

The years in Cape Town would be the most fulfilling and challenging of her life. With the widowed governor of the Cape, Lord Charles Somerset, a former army officer and younger brother of the sixth Duke of Beaufort, she began a passionate and enduring relationship, possibly platonic, very probably sexual, although it is not known, nor is it appropriate that we should know, as we have no proprietary right to Barry and her private life, how that sexuality was expressed. Certainly it was thought to be true when a placard was posted in Cape Town on Tuesday the first of June, 1824, claiming that a witness had seen “Lord Charles buggering Dr. Barry.”

Lord Charles Somerset

Barry, walking along Heerengracht that morning, heard the story and behaved like any sensitive human being whose life had been rocked to its foundations. She sought refuge in a nearby shop and broke down in tears: of rage that something so precious had been publicly and libellously defiled; of fear that she and Charles would be arrested on charges of sodomy, a crime in the armed forces that was punishable by death; of exoneration, if investigated, by the disclosure of her sex, by which she would lose everything of significance, including her identity, her commission and her vocation.

There was a court of inquiry but no conclusive evidence was produced, and the case was closed. The libellers were never identified, although Somerset and Barry, as well as citizens of Cape Town, offered substantial rewards. But the shadow and the shame never entirely dissipated, and Lord Charles Somerset was ordered to England in February of 1826, with his second wife and his family, to respond to criticisms of his administration. Barry remained at the Cape, more argumentative, more confrontational, and more intolerant than ever, vulnerable without her champion, Somerset, who had wielded his considerable influence to extricate her from every crisis into which her ferocious temper propelled her: challenging authority and incompetence and imagining insults and conspiracies until the Office of Colonial Medical Inspector was abolished. Shattered, she resigned her appointments and practised medicine privately, caring with a brisk compassion for the Cape garrison of 2,400 officers and men and their wives and children.

James Barry, evocative but unauthenticated portrait

On Tuesday, June 25th, 1826, Barry was summoned in the middle of the night to attend Wilhelmina Munnik, in protracted labour and dangerously exhausted: she was unable to give birth naturally, and the only alternative, to save the living fetus, was to perform caesarean surgery, which almost invariably resulted in the death of the mother and, all too frequently, the child. Only in three recorded cases of caesarean section had both survived.

Barry, with Wilhelmina’s consent, and meticulous attention to hygiene and technique, that night performed the first caesarean surgery in the Cape Colony. Wilhelmina and her son survived, and the baby was christened James Barry Munnik, a name that would be handed down through generations of the Munnik family, in tribute to the surgeon who had delivered him.

In August of 1829 Barry, now a full staff surgeon in Mauritius, received devastating news. Charles Somerset, some twenty-two years Barry’s senior and suffering from the complications of heart failure, was reported to be dying. Barry, characteristically, committed one of the flagrant breaches of discipline for which she had become notorious and abandoned her post without permission. She reached England on Saturday, December 12th. Somerset was still alive, although very frail, and Barry, who had saved his life years before, nursing him with tenderness and dedication through a near-fatal attack of typhus with dysentery, undertook his care. Somerset seemed to rally, and then died on Sunday, February 20th, 1831, with his wife, Lady Mary, his daughter Georgiana, and his beloved Barry at his bedside.

For Barry without her patron, “my more than father— my almost only friend”, the aftermath and the years that followed were a blurred succession of postings, to St. Helena, Jamaica, Trinidad where she fell ill with malaria and was discovered sweating and delirious in bed by two medical subordinates who examined her and saw indisputable evidence of her sex, and maintained their silence; to Malta and a cholera epidemic; to Corfu; to the hostile meeting with Florence Nightingale at Scutari; and eventually to Montreal, where one officer was overheard to remark, seeing her for the first time, “You’d have to be mad to take that for a man.” As intransigent as ever and suffering frequent bouts of bronchitis and pneumonia, she reached the pinnacle of her career and fell abruptly and catastrophically from it while pursuing personal vendettas. She had always been defensive and impulsive: at the Cape in her youth she had struck an officer across the face with her riding crop when he had said, “By the Powers! You look more like a woman than a man!” And she had fired a pistol with deadly intent in a duel when another officer had challenged her after some imagined slight and been shot herself, a wound she had dealt with in private. But this time Barry had gone too far, expressing her volatile opinions to the Dean of Montreal, the bishop and the archdeacon, as well as other members of the clergy, and “assailing them with violence and insulting conduct”. Tolerance of her increasing eccentricity had reached its limit. She was recalled to London and faced a medical board comprised not of the director-general and senior officers to which her rank, the equivalent of brigadier-general, entitled her, but three “junior surgeons who were perfect strangers to me and to my peculiar habits…. they not unnaturally and somewhat hastily jumped to the conclusion that I was in a bad state of health.”

The board’s decision was also a foregone conclusion. James Miranda Barry, now officially sixty years of age and in reality several years older, was relieved of her North American command and reduced to half-pay.

There was no appeal.

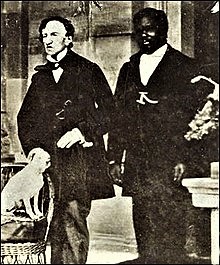

Barry in Jamaica with John and her dog Psyche

She drifted, lost, no longer defined by the identity she had created and the persona she had inhabited for so many decades. She travelled to the Caribbean with her Jamaican servant, John, a former soldier in the West Indian Regiment, chasing the ghosts of the past, considering adopting a child, visiting old friends, too many of whom were dying or infirm; becoming increasingly unwell herself; returning to London and more shadows and memories of the past.

In the early hours of Tuesday, July 25th, 1865, in sweltering heat, Margaret Anne Bulkley, who for fifty-six years had lived as James Miranda Barry, died of cholera. Years before, in Trinidad, she had told a female friend— and Barry had many female friends, and was sparkling and gregarious in their company— that in the event of her death her body was to be wrapped in the sheets in which she had died and buried unwashed and unexamined. That wish was either not known or ignored by those who came to lay out the corpse of Dr. James Barry before the arrival of the undertakers. The revelation of her sex to the press created an international sensation.

Dickens gave the story a fictional spin in 1867. In 1919 the renowned actress Sybil Thorndike played Barry on the stage. There have been novels, biographies, broadcasts: a film is said to be in production.

Barry has been appropriated by gender activists who attribute to her various sexual identities, and who demand that the male pronoun be used when referring to her, “as that was what he insisted on during his lifetime.” Frankly, it would be absurd to imagine any one, under the circumstances, referring to Barry during the course of a life lived in male disguise as anything other than he. The possibility of Dr. James Miranda Barry being female, although suspected by many and known with certainty by a few, was simply so remote as to be unthinkable.

Barry never played the gender card in her lifetime, and it is impertinent to impose upon her the sensibilities of the 21st century. Nothing diminishes her uniqueness: as the first woman ever to hold the rank of general in the British army, as a pioneering surgeon, as a fearless human being sacrificing comfort, peace, stability, and emotional and physical intimacy in the pursuit of her destiny.

She had chosen her life. But the battered trunk which had accompanied her for so many years, when opened after her death by the solicitors in charge of settling her affairs, may speak of yearning and regret. When lifted, the lid’s leather lining was found to be covered with a collage of women’s fashion plates. Hats, gowns, hairstyles… a haunting affirmation of an irretrievable past, and an acknowledgment of the woman, long forgotten, who had once lived it.