DOUGLAS REEMAN: THE MAKING OF A STORYTELLER

14 Oct 2024

The North Sea on a November night in 1942: a motor torpedo boat, badly mauled by E-Boats off the Hook of Holland, is taking on water. Her skipper is a Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve lieutenant aged twenty-eight; his second in command, an RNVR sub-lieutenant, has just passed his eighteenth birthday. Both men, and their crew of volunteers, know that death is only minutes away.

The boat sinks. There is no time to set her depth-charges to “safe”, and as she goes down they explode, killing and maiming the men in the water. The living and the dead drift together in their life jackets, red lights rising and falling on the swell.

The air is bitter, the sea repeatedly slapping the face of the eighteen year-old subbie, who is kept conscious only by the icy water and the occasional sip of brandy from his skipper’s hip flask. There is no pain; he is unaware of his internal injuries, or that his scrotum has been split by the blast. He knows only that nobody is looking for them: nobody at the base knows where they are, and no one will come.

When the dawn came, a sunless mist on the sea’s face, only four men were still alive.

The throb of engines might have been one final hallucination… then the black and yellow hull of an RAF air-sea rescue launch emerged from the haar… throttled back now, drifting, dead slow, among the red lights on the water.

They called him the Fisherman, the flight sergeant in command of the launch, because he fished men out of the sea, sometimes living, too often dead. Usually they were airmen, Allied and Luftwaffe, sometimes clinging together to the same wreck buoy. He seldom found survivors from Light Coastal Forces, and had received no signal from the base at Felixstowe that an MTB was missing. Only fate or instinct had brought him here today.

It was the Fisherman who hauled Douglas aboard on the morning of November 13th, 1942, and who roughly and efficiently sutured his torn scrotum. He bore that scar, with others, for the rest of his life.

But he was young and resilient and desperate to rejoin his flotilla, and when he had healed sufficiently he went back to war. The Mediterranean: following the Eighth Army along the coast of North Africa. Running guns to Tito’s partisans in Yugoslavia. Sicily. Italy. “I saw planes falling into the sea like leaves.”

…. June 12th, 1944: D-Day plus 6. An MTB liaising between the British on Gold Beach and the Canadian Third Division on Juno is caught in a fast-falling tide on an underwater anti-tank obstacle just off Arromanches. She is being straddled by semi-armour piercing shells fired from inland. Her captain, another old-young man in his late twenties, sends his lieutenant over the side into the sea with a few volunteers to try to lift the boat off. The shells bracket her, “salt water cascading all around, ice-cold, tasting of cordite.” Another of the flotilla shouts through a loudhailer, “Bale out! The bastard’s got you zeroed in!”

The last shell rips low across the water, flat trajectory: a direct hit amidships. The MTB, dried mahogany and high-octane fuel, goes up like a bomb.

The young lieutenant is drifting in the shallows, his legs on fire: white phosphorus can burn through bone, and is reignited on contact with oxygen. The world is a fireball… smoke, stench, screams, falling fragments, human torches extinguishing themselves in the sea.

Salt in his eyes. Rain. Cold. Hands dragging him out of the water and onto the beach. Some one was saying, “It’s OK, buddy. Take it easy,” and some one else was saying, “Keep that rain out of his face,” and some one else said, “Somebody give him a cigarette.” And because it seemed important to him to make the distinction, he said, “I smoke a pipe,” before the morphine took him under.

They were Canadian army medics and they saved Douglas’s life, put him on a landing craft filled with other wounded, and sent him back to England. “The drab field ambulances were waiting,” he wrote. “They always were.”

Many years later he wrote of the hospital, the long polished corridors down which damaged young men with bandaged heads and eyes and limbs or parts of limbs hurled chamberpots as curling stones, and “you didn’t want them to move your bed, because the closer you got to the end of the row the more serious it was, and the bed at the end of the row by the door was always empty the next morning.” It was there that a harassed doctor handed him a pair of crutches and told him to walk on his burned feet, but “you’ll always have a limp, of course.” “I thought, sod you, no, I won’t.” It was from that hospital that he escaped on an afternoon pass to the local cinema, walking with the crutches. He dropped one and tried to pick it up, “and I fell over and burst into tears. I’d just had enough.”

But he walked on the scarred feet, day after day, discarding first one crutch and then, after a long time, the other. “Sheer bloody-mindedness,” he said. “And I didn’t have a limp. I refused to limp.”

They sent him from that hospital to Iceland to recuperate. And there, in an atmosphere tinged with insanity and the blackest imaginable humour, his “light duties” included hunting U-Boats, accompanying on his rounds the rating who delivered mail by dogsled, and learning how to type (“Right, Reeman, this is the telephone directory. Sort it out, and make sure the Admiral is Number One.”) “We were all half mad,” he told me. “All of us were wounded and most of us were bomb-happy… one subbie was so nutty he used to sit naked on a pile of coal in the snow and howl at the moon. His balls froze to the coal one night.” When I finally managed to stop laughing, I said, “You really should write about this some day.” “Nobody would believe it,” he said.

And when they saw that he was more or less rehabilitated, they sent him back to war. And eventually, in May of 1945, to Germany and the world of The White Guns, perhaps, with A Prayer for the Ship, one of the most autobiographical of his novels. Everything in The White Guns is drawn from Douglas’s personal experience: the crimes, the criminals, the rackets, the black market, the rioting that becomes deadly, the firing squad of which he was in charge; his love for Ursula Geghin, whose real name was Gisela, his dear friend “John Kidd”, whose nickname really was Beri-Beri (“I can’t think of anything else to call him,” he said to me. “He’s just Beri-Beri to me.” “Then you’ll have to call him Beri-Beri,” I said. “I’m sure he wouldn’t mind.”) His petty officer driver Max became Heinz Knecht, chosen for the job because he was the only German honest enough to admit to Douglas that he had been a member of the Nazi party. The psychopathic Cuff Glazebrook and the justifiably bitter Jewish RNVR commander, Meikle, had their real counterparts in Douglas’s life, as did the senior Kapitän-zur-See Manfred von Tripz, who inspired the characters of Felix von Steiger in The Last Raider and his son Rudolf Steiger in With Blood and Iron. Douglas knew them all, and they remained in his mind long after he had exchanged one uniform for another and was walking the beat as a Metropolitan Police constable in London’s heavily bomb-damaged East End.

And there, as he had from his childhood when he spent the weeks aboard the troopship from Southampton to Singapore chatting to the soldiers (“Don’t talk to them, my mother said. I suppose she thought I’d pick up bad language or something. But I did talk to them”) and as he had during the war and in immediate post-war Germany, he talked to people, made friends, asked questions, and remembered everything he was told. Bookies and barrow boys, prostitutes, tick-tack men at the dog tracks, publicans, other cops, and the tough young thugs who had served in the same theatres of war and who wore the same medals, and who more often than not were carrying firearms they had smuggled back into England in their kitbags. And people sensed that his interest in them was genuine, and they responded and entrusted him with their stories. He made a note of their idiosyncrasies, their turns of phrase, their local dialects, their physical quirks: the night watchman on Douglas’s beat who always had a cup of tea waiting when he passed, and who regaled him in a voice barely louder than a whisper with stories of his life as a prizefighter, inspired Douglas to create the character of Mark Stockdale, Richard Bolitho’s first coxswain, whose vocal cords were so damaged by years of bare-knuckle fighting that “he spoke very little, and then only with a husky whisper.”

And then the Korean War broke out, and after five years on the beat and as a plainclothes detective in the Met’s Criminal Investigation Department, Douglas returned to the Royal Navy and the life which had come to define him. “Would I have been the same person if the war hadn’t happened? Of course I wouldn’t. I would still have been a writer, I think… but it made me. And I wouldn’t have missed it for the world.”

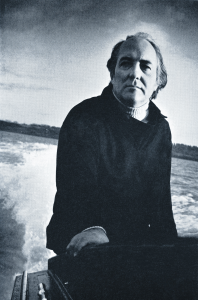

It was not without cost to himself. He knew firsthand what fire and water and blast and metal and chemical could do to the human body, and to the mind and spirit: in a photo I cherish, which was taken immediately after the war, his face is gaunt and deeply lined; the mouth smiles, but the eyes are bleak and shadowed. His dark hair is greying at the temples, and his sideburns are grey. He is twenty-one years old.

He was never bitter toward the enemy, and he never thought that he would be killed, but I saw the scars he bore with such grace and gentleness and good humour, and the memories never left him. I remember one afternoon in London before we were married: I was still very young then, and naïve, and I remember the man walking toward us from whose face I looked away. It was less a face than an inexpressive mask, a structure of bone over which the skin seemed too tightly stretched. Douglas did not look away. And I sense now, in retrospect, the recognition and acknowledgment that passed between these two men of the same generation, and the beautiful compassion in Douglas’s voice when I asked later if he had known him. “No,” he said. “But I know he was a very brave man.” And he told me about the Guinea Pig Club, and Archibald McIndoe’s pioneering reconstructive surgery and rehabilitation during the war of thousands of Allied airmen at his dedicated burns hospital in East Grinstead, Surrey. He said, “There but for the grace of God go I,” and in that moment I see the birth of Commander James Tyacke, disfigured at the Nile, who becomes Richard Bolitho’s flag captain.

He was a storyteller: that was what he called himself, and that is how he would want to be remembered. He saw the past and illuminated it so that it became real and vivid and immediate: he spoke for those who had fought and survived or died in his own war and in his father’s war, and in his grandfathers’ wars, and in Nelson’s, and he told the stories of people who would not, or could not, speak of their experiences. He never flinched from the truth, although there were events and scenarios he refused to depict, and facts he would not divulge. “It wouldn’t do anybody any good,” he said. “Nobody really wants to know how their son or their brother or their husband died. Nobody needs to know.” I said that it was his duty to bear witness to the truth of war, no matter how horrific, but perhaps he was wiser than me. Perhaps some truths are better left unspoken.

One afternoon close to the end of his life, he was fretful and anxious, not for himself but about his work. He asked me, “Will it all be forgotten?”

I said, “It will never be forgotten.”

Rest easy, my captain. I have the watch. You gave me the gift of your life throughout the years we shared, and I remember everything you told me, and everything you taught me. Eyes on the compass and on the horizon… a grey mist on the sea’s face… another grey dawn breaking.