Eulogy

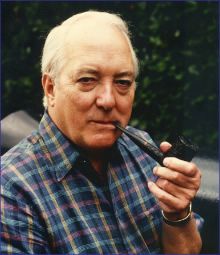

On February 15, 2017, Douglas Reeman’s life was celebrated at St. Andrew’s Church in Cobham, Surrey. During the service, his long-time friend Christopher Hall presented the following eulogy.

Douglas Reeman, or The Admiral as he was more affectionately known, was born on October 15, 1924 into an army family living in Thames Ditton, and despite his great love of travel he never strayed from his Surrey roots.

Douglas Reeman, or The Admiral as he was more affectionately known, was born on October 15, 1924 into an army family living in Thames Ditton, and despite his great love of travel he never strayed from his Surrey roots.

When he was six, he was touched by fate for the first time: his father was posted to pre-war Singapore, and the three Reeman boys and their mother went by sea to visit him. As soon as the engines started aboard that trooper and the sea air hit the young Douglas, he was smitten by the sea, and throughout the voyage in characteristic fashion he ignored his mother’s edict, “don’t talk to them”, preferring to pay close attention to the no doubt colourful conversation of the soldiers on board.

Douglas was enchanted by Singapore and remained in love with the Far East all his life, and when he came home, the six-year old asked his maternal grandfather, Ted Waters, an old soldier, himself, to take him to visit HMS Victory. A novelist was born.

When he was sixteen he joined the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve – the “wavy navy” – and remained proud of that all his life. He saw action in destroyers and motor torpedo boats in the North Sea, the Arctic and the Mediterranean, and was twice sunk, twice blown up, and twice mentioned in dispatches.

On VE-Day, Douglas was in Copenhagen being swarmed by cheering Danes, and three days later he was in Kiel when the German navy surrendered. And being Douglas, he talked to the German sailors and to U-boat officers and made friends with them, and later he would write their stories, sometimes from the German point of view.

Perhaps because of the brotherhood of the sea or because he was simply a wonderful man with compassion, insight and a generous spirit, the Germans became and remain his second biggest audience after the English-speaking world, with the Japanese his third-biggest audience. The irony was never lost on Douglas.

He was recruited by the Metropolitan Police while in Germany, and came home to walk the beat in London’s heavily bombed East End as an uniformed constable and later as a plainclothes detective. Douglas talked to people there too, and they told him their stories. When asked, more than once in later years, what it takes to be a good writer, he answered, “Be a good listener.” And he was.

When the Korean War broke out in 1950, Douglas went back into the navy, because at heart he was a naval officer. On his return he worked for the London County Council as a children’s welfare officer.

It was about this time that Douglas bought a boat, the MV Guardian, and one day whilst working in the boatyard with a friend, whilst listening to a story being read on the radio, he said, “I could do better than that!” The friend said, “Well, why don’t you try then?” Douglas replied, “I don’t have a typewriter.”

So the friend went off and bought him one, an ancient monster that still sits in their loft today, and on that typewriter, on the back of London County Council notices pilfered from the office in the best possible police manner, he wrote the story of “his” war, and called it A Prayer for the Ship.

The manuscript was sent to three publishers, one of which had published a book he greatly admired called Proud Waters by Ewart Brookes, about minesweepers. After waiting three months, Douglas received a summons from the publisher, who said, “We quite like it. Here’s a contract for this book and two others.”

With that, Douglas Reeman walked out onto the street and said to the nearest crowd waiting at a bus stop: “I’m a writer!” And so he was. A Prayer for the Ship was published in 1958 and is still in print.

Ten years later, as Douglas kept talking to his American publisher Walter Minton about Nelson’s navy, he was challenged to write about the subject; and during a trip to Jersey in his boat he met a rather fearsome army type who’d taken his mooring lines and helped him make fast in Gorey harbour. This man introduced himself as Richard Bolitho – the brother of the then Lord Lieutenant of Cornwall.

Douglas named his solitary, sensitive, compassionate hero of what was to become a new best-selling series Richard Bolitho, written under the pen name Alexander Kent, who had been his boyhood friend and fellow naval officer, and who had been killed during the war.

He wrote twenty-eight Bolitho novels over the years and nearly forty novels of the more modern navy under his own name. All are still in print, and are published in nearly twenty languages. His publishers estimate 34 million copies have been sold.

His books have touched the lives of hundreds of thousands of people of all ages, and in every walk of life. It was on a book tour across Canada to promote A Ship Must Die that Douglas locked eyes on a beautiful woman in the audience. Her name was Kim. They fell in love, and remained inseparable soul mates until the end. If love is immortal, the love they shared will never die.

I first met the Admiral about fifteen years ago when I was working as a carpenter building a boiler house next door. I was often invited to the “bridge” when the sun had gone over the yard arm to talk about life and listen to his stories, all told with his unique dry sense of humour and one-liners.

On one occasion, Douglas gave me a signed copy of a Bolitho book which had just been published: In the King’s Name. He said, “Hall III,” as I was known to him, “you might recognise someone in this.” When I got to page sixteen, I read the line: “the tallest person present was the new carpenter, Chris Hall.” Fame at last, I thought, until I realised it was nearly two hundred years earlier, but proud to be recognised.

During the time this book was being written Douglas asked me if I could restore his precious cannon, as it was about to slip below the waves. It was one of two which survived the making of a television series called I Remember Nelson, on which the Admiral had acted as a technical consultant, and it resided in pride of place in his garden.

I gave him a quote for making an exact replica made of Douglas fir, which came from Canada. Needless to say, he asked me to build it.

The values by which Douglas lived, which he called OLQs, officer-like qualities, courage, compassion, honour, duty, responsibility, recently described to Kim by a reader in an e-mail of support as “men, mission, self”, suffuse those books and were exemplified by him.

Douglas Reeman was and will always be the very essence of a naval officer, and in both senses of the word he was a gentle man and a gentleman.

We shall all miss him.